Inmates inside Mississippi’s state prisons are describing inhumane and dangerous conditions that have them fearing for their lives, including overflowing raw sewage covering their cell floors, lack of access to showers for weeks and deadly gang violence.

At the state’s most notorious prison unit, one inmate says he’s living in a “death trap” and is eager for Unit 29 of Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman to close, as promised by the state’s recently installed governor.

“I’m sitting here waiting to get away from this place. People are going to continue to lose their lives here,” said an inmate who CNN is identifying as Charles, speaking by phone from Unit 29. “It needs to be shut down. Our lives are at stake.”

Charles is a pseudonym for the inmate, who did not want his identity revealed for fear of retaliation. Prisoners are prohibited from having mobile phones, but videos purportedly captured on inmate cell phones can be found all over social media.

The state Department of Corrections has acknowledged contraband cell phones are an issue. State Rep. Donnie Bell has authored a bill that would command sentences of three to 15 years for any prisoner or DOC employee caught with a cell phone.

Nine inmates have died at Parchman in a little more than a month, most of which as a result of either violence or suicide. As of January 17, Parchman held 2,815 of the state’s more than 19,000 prisoners.

Gov. Tate Reeves announced during his first State of the State address that he will shutter Parchman’ Unit 29 — his words coming weeks after prison officials said they’d relocated 375 violent prisoners and were seeking cells for 625 more Unit 29 inmates.

“There are many logistical questions that will need to be answered. We’re working through that right now, but I have seen enough. We have to turn the page,” Reeves said. “This is the first step.”

Stabbed in the eye

Many inmates possess knives, Charles said, and his biggest fear is being killed during an altercation on his cell block — something he says occurs regularly.

“The gang violence is at an all-time high here. I just try to stay out of the way. I don’t want to be stabbed. Certain inmates have huge knives made out of whatever they can find,” he said. “I’m trying to make it home to my family.”

The mother of another Parchmaninmate, who CNN is identifying as Shantal, said her son was scheduled to be released in January, but he was injured in a gang altercation and landed in the prison hospital.

“That night when the melee started over at (Unit) 29 … he got stabbed in his eye. We don’t know how, when, where or why because we can’t talk to him,” she said.

Shantal spoke with CNN over the phone and requested anonymity out of fear for her son’s safety. Prison records indicate he has been transferred to Unit 29 after spending time at Parchman’s hospital.

The disturbances began December 29 at the South Mississippi Correctional Institution where one inmate was killed and two were injured, which led the state DOC to place its facilities on lockdown.

The restrictions on prisoners’ movement and visitation did little to quell the violence. In the following weeks, four more violent deaths were reported at Parchman and another death was reported at the Chickasaw County Regional Correctional Facility.

“Gangs are at war,” the local coroner told the Clarion Ledger newspaper.

Corrections officials confirmed in a news release that some of the violence in the prison system was “gang-related.” The chaos escalated that week when two inmates at Parchman prison escaped. They were captured days later.

“I am absolutely scared for my child. I’m scared for him and for the rest of them, too,” Shantal said.

The lockdown was lifted January 10, except at Parchman.

Guards belong to gangs, prisoners say

CNN spoke with several Mississippi inmates, all on the condition of anonymity because they fear retaliation. They paint a picture of a chaotic, violent place where little value is placed on life.

They describe inhumane conditions and abject squalor, and say the prisons are overrun with gangs — both inside and outside the cells.

“Man, it’s way bigger than gangs. It’s the administration,” said Jordan, an inmate at Wilkinson County Correctional Facility. “The administration in these prisons are the biggest gang … Some guards, they come here, and they’re already affiliated with gangs.”

Jordan spoke with CNN on a cell phone he says he purchased from a fellow inmate, who bought it from a prison guard. Jordan and Charles accuse the correctional officers of enabling the violence between inmates and allege that some of the guards are affiliated with the gangs who “run the prison.”

“I don’t feel safe due to the administrative staff,” Charles said. “Some of the people are affiliated with (gangs). They were known to give keys to inmates and let them come in on certain inmates, and stab and kill them.”

Given four business days to respond, the DOC and governor’s office have not responded to CNN’s requests for comment.

Management & Training Corp., which runs the Wilkinson County prison, did not return calls or emails Tuesday, but spokesman Issa Arnita told the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting in July that reports of gangs running its prison were untrue.

“At no point have we ever conceded control of the (Wilkinson) facility to gang leaders,” Arnita said. “That in no way is the reality at the prison.”

The governor, after visiting Parchman and another state prison January 23, announced immediate changes, including screening prison guards for gang affiliation, relocating prisoners to different housing units and jobs, and cracking down on contraband cell phones.

Inmate: Sewage water everywhere

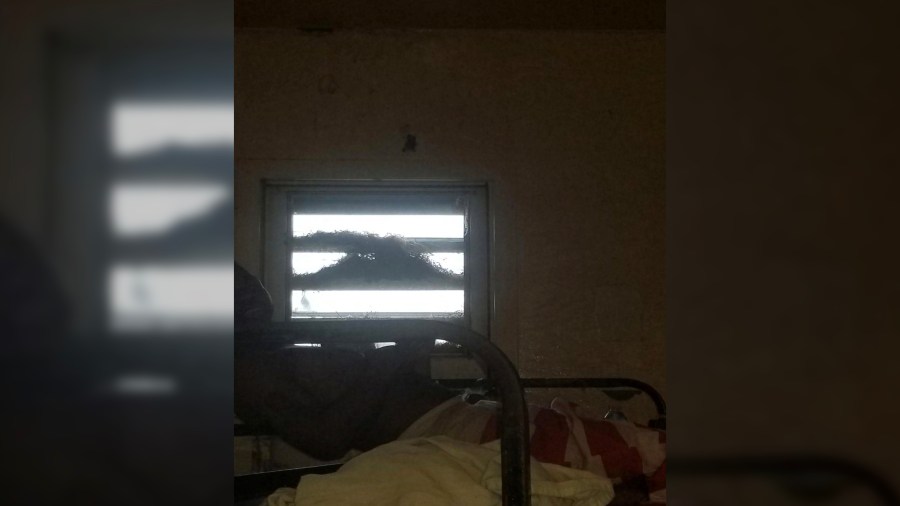

Parchman’s failing infrastructure was detailed in a 154-page report by a state health inspector who visited in June 2019 and noted mold growing on walls, inoperable toilets, a handful of cells with no water and dozens without electricity.

Maintaining hygiene is nearly impossible, Charles said.

“I haven’t had a shower in over two months,” he said. “We have to take bird baths in the sink, if you can get the water to run.”

While the spotlight has been on Parchman because of the recent spate of violence, crumbling infrastructure and poor conditions are a statewide issue in Mississippi prisons.

Jordan shared cell phone video of sewage water flowing through his cell and said it took more than a week before the problem was addressed: “We walked around for nine days with raw sewage up to our ankles.”

“They used a squeegee … (to push) the water out of our cells over into the shower area. We begged them for bleach … so we could clean ourselves. We didn’t receive cleaning supplies, but the toilets continued that night — they started back overflowing.”

Jordan also shared video of mold growing on the wall beside his bed. He is concerned about his health, he said.

“I had been having trouble breathing,” he said. “They didn’t clean up the mold. They just took my sheets. They took my blanket. They took my pillow. They took all that and gave me new stuff, but the mold is still here on the wall. It’s still here.”

Money long at the heart of problems

Disturbing conditions at Parchman aren’t new. A court case outlining troubling conditions in the state prisons was partially closed in 2011, almost 40 years after it was filed. State funding and personnel shortages followed, ushering in a return of worrisome environs at the state’s prisons.

In closing the portion of Gates v. Collier that pertained to state prisons, US Magistrate Judge Jerry Davis applauded Mississippi for the strides it had made since the case was filed in 1971. Among the strides was meeting the American Correctional Association’s accreditation standards,

“The people of Mississippi should not think that their prisons have been converted to ‘country clubs.’ They are prisons where no citizen wishes to be incarcerated,” the judge wrote in 2011. “However, they are humane and do not systemically subject the inmates to ‘cruel and inhuman punishment.’ That is the mandate of the Constitution and why this court has been involved for all these years.”

The state upped the prison system’s funding in following years, from an estimated $312 million in fiscal year 2011 to $359.7 million in fiscal 2015, state budget documents show. The Legislature reduced the funding thereafter, allotting $334.6 in fiscal 2018 and $344 million last year.

Of the department’s $419.1 million request for fiscal 2021, lawmakers are recommending a budget of $332.5 million to the DOC, according to budget documents.

In her fiscal 2021 budget request, then-DOC Commissioner Pelicia Hall, who stepped down last month, asked for $22.5 million to repair Parchman’s Unit 29, as well as $35.6 million to fill 800 vacant positions at three state prisons.

“The number of officers has continued to dwindle as the agency’s pay has not kept pace with industry salaries and other professions,” a DOC news release said, adding that officials would like to raise correctional officers’ starting pay from $25,650 to $30,370, which would bring Mississippi in line with its four neighboring states.

Star turn

As the department struggles with funding shortfalls, conditions inside the holding facilities have drawn the scrutiny of rappers Jay-Z and Yo Gotti, who are helping more than two dozen inmates sue over the state of prisons. In a recent motion, the inmates asked for an emergency protective order to allow an independent agency to take over the day-to-day operations.

The motion quotes health specialist Debra Graham, who noted that sewage in the prisoners’ eating and living quarters poses “serious and even lethal health risks.”

The lawsuit filed last month cites the Legislature “dramatically” reducing prison funding and says the conditions violate prisoners’ constitutional rights.

“The Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution prohibits the infliction of cruel and unusual punishment and is violated when prison officials fail to protect against prison-related violence and when prison conditions fail to meet basic human needs,” it says.