(CNN) — Because of their small size, water beetles might have been kicked around since they were born — but thanks to abnormal survival strategies, they’re “stayin’ alive” after predators eat them.

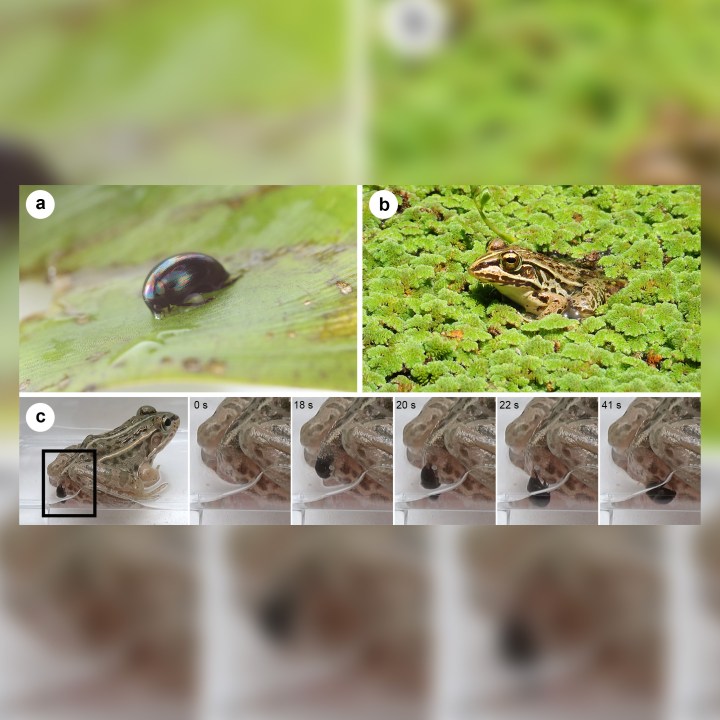

Meet the aquatic beetle Regimbartia attenuata, which can survive a journey through a dark-spotted frog’s gut and exit alive through its feces, according to a study published Monday in the journal Current Biology.

The pressure of being hunted is typically what leads to the evolution of different escape behaviors in prey animals. Surviving the extreme conditions of an animal’s digestive system is a wild card that depends on the prey animal’s ability to move quickly through to the, ahem, escape hatch.

Such a deadly environment could impose speedy and active escape behaviors on swallowed prey species — so Shinji Sugiura, the author of the study, tested this hypothesis with aquatic beetles and dark-spotted frogs.

After the frogs swallowed the beetles, 90% of the insects were excreted within six hours of being eaten “and, surprisingly, were still alive,” said Sugiura, an associate professor in the department of agrobioscience at Kobe University in Japan, in the study.

In a second experiment, beetles whose legs were fixed together with wax were all killed and inside the frogs’ digestive systems for more than a day — indicating that the first beetles might have used their legs to actively and quickly escape headfirst from the frogs, rather than being passively released through the frogs’ waste.

Most prior studies have analyzed how prey animals escaped before contact. This study “is the first to document active prey escape from the vent of a predator and to show that prey may promote predator defecation to hasten escape from inside the predator’s body,” Sugiura said.

The race to escape

The aquatic beetle R. attenuata is common in wetlands where the dark-spotted frog (Pelophylax nigromaculatus) abundantly resides. Because this frog species eats both land and water insects, it’s a potential predator of these specific aquatic beetles.

To investigate how the beetles responded to being eaten by the frogs, Sugiura provided the frogs with the beetles in plastic bins. The frogs swallowed all 15 of the beetles but excreted more than 93% of them within four hours afterward. The beetles often exited entangled within the frogs’ feces, but then quickly recovered and swam around freely. This same escape behavior happened with four other frog species, but some beetles had slightly lower rates of success.

When the dark-spotted frog was provided a different aquatic beetle (Enochrus japonicus), all swallowed beetles were killed and excreted more than a day later — suggesting that aquatic beetle R. attenuata had a survival advantage over its cousins.

Physical adaptations including a compact, drop-shaped body and the ability to curl down their heads may “help the beetles to survive the way through the frog’s digestive system,” said Martin Fikáček, a researcher in the department of entomology at the National Museum in Prague, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Such kind of adaptation is called exaptation,” he added in an email. “It evolved for another reason (likely for improving the swimming skills and protecting the beetles from predators) but it may at the same time help them to survive and easily go through the frog’s intestines.”

Since R. attenuata use their legs to swim, Sugiura thought their legs might play an important role in their ability to escape from the frogs’ guts. He provided the frogs with water beetles whose legs he fixed together with sticky wax, and those beetles weren’t so lucky — all were killed within the frogs’ digestive systems and eventually excreted as feces more than a day later.

Evolving an unusual survival strategy

When many animals close in on their prey, they use their teeth to crush them. Because frogs lack teeth, they rarely kill their prey before swallowing them — so their digestive systems are crucial in killing and deriving any nutritional benefits from their victims.

The dark-spotted frog’s digestive system is a long, tube-like structure that consists of an esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. It starts at the mouth and ends at the vent (anus), just like a human. Since killed water beetles (with their legs fixed) took more than a day to exit the frog and the surviving water beetles took a successful minimum of six minutes, Sugiura concluded that the latter’s exit must have been an active escape rather than dependent on the frog’s waste.

“R. attenuata cannot exit through the vent without inducing the frog to open it because sphincter muscle pressure keeps the vent closed,” Sugiura said. “R. attenuata individuals were always excreted head first from the frog vent, suggesting that R. attenuata stimulates the hind gut, urging the frog to defecate.”

Having to adapt to an aquatic environment with predators could have led to the beetles’ ability to survive inside frogs, the study said.

“Frogs tend to swallow their prey whole, so any breakdown of body parts would occur in the digestive tract,” said Matthew Pintar, an aquatic ecologist at Florida International University who wasn’t involved in the study, in an email.

“Beetles tend to have tough exoskeletons relative to most insects, and many aquatic beetles in particular carry their own air to breathe from. Both of these characteristics may help prevent digestion if they are able to quickly move through the frog’s digestive tract, which R. attenuata is capable of.”

These features altogether may give the beetles a second chance at life.