(CNN) — You’ve likely heard of a “flesh-eating bacteria” hitting Florida and other states this summer. While the bacteria are real, public health officials say the “flesh-eating” part is not.

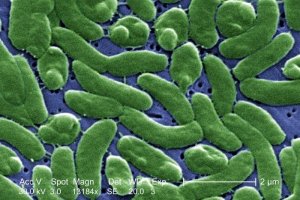

Vibrio vulnificus is a naturally occurring bacterium that lives in warm saltwater and infects humans through the consumption of undercooked shellfish and skin wounds. Four infections have been reported in Texas so far this year, along with 13 in Florida, six in Maryland and 10 in Mississippi.

In extreme cases, the bacteria can lead to blood infections (half of which are fatal, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), possible amputation and blistering skin legions.

Only bacteria classified as group A strep are technically “flesh-eating,” says Rajal Mody, a medical epidemiologist in the CDC’s Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases. The dozen species of Vibrio bacterium known to cause disease in humans are not in this group but do account for an estimated 80,000 illnesses, 500 hospitalizations and 100 deaths each year in the United States.

The difference is that flesh-eating bacteria attack the bands of tissue that surround muscles, nerves, fat and blood vessels. Vibrio vulnificus, on the other hand, gets into the blood stream from either the skin or intestinal tract, and can damage organs and cause skin lesions that may appear similar to the skin damage caused by strep A, Mody says.

Because Vibrio vulnificus multiplies in warmer water temperatures and tends to reach peak levels in midsummer, according to Mody, the higher bacteria count coincides with the height of beach season. And no one wants to get a limb amputated while on vacation.

“The important thing to remember is that these infections are rare,” Mody says.

The CDC estimates that nationwide there are 95 Vibrio vulnificus cases each year, including 85 hospitalizations and 35 deaths. And typically the bacteria are only a summer health hazard, with 85% of infections occurring between May and October.

Most at risk for severe illness and death from Vibrio vulnificus are people with a weakened immune system or who suffer from chronic liver disease, Mody says.

Milder symptoms caused by this bacteria include diarrhea, vomiting and stomach pain. Some people might not show any signs of infection. Two parasites found in contaminated water, Cryptosporidium and Giardia lamblia, can also cause similar symptoms, according to the EPA.

Still, shooting that raw oyster or cutting your foot on a shell during your beach vacation shouldn’t be taken lightly. If you experience symptoms a few hours or days after eating shellfish or being exposed to coastal water, seek medical attention immediately.

“Rapid treatment is really critical,” Mody says. “If someone is eating raw oysters, especially in a high-risk group, or is swimming in the ocean and notices skin lesions that are worsening quickly, it is important to get early treatment. Mortality rates increase if treatment isn’t started on the first day of symptoms.”

For those concerned about the safety of their summer vacation spot, states that typically report the most infections are Florida, Texas and Maryland. In 2013, the Florida Department of Health reported 11 deaths and 41 infections. Texas reports 15 to 30 annual cases, while Maryland state officials say they see an average of 25 infections per year.

California took action in 2003 to reduce health risks by implementing a regulation to restrict the sale of raw oysters harvested from the Gulf Coast during warmer months when the bacteria count tends to be higher. In a review published in 2013 by CDC and the California Department of Public Health, researchers found that this action was strongly correlated with the reduction of deaths and illness.

Mody says based on the data, it can be assumed that oysters harvested in the Gulf of Mexico between April and October have the highest levels of the bacteria.

In addition to avoiding raw oysters, the CDC also recommends wearing gloves when handling raw shellfish and thoroughly cooking it, and discarding closed-shell varieties that don’t open after cooking.

For visitors to the beach or bay, if you have an open wound or broken skin, avoid exposure to warm salt or brackish water if you’re in a high-risk group.