TUCSON, Ariz. — (StudyFinds.org) – A microchip attached to a bone in your body may be the future of preventing osteoporosis. Scientists from the University of Arizona have developed an ultra-thin computer which they hope will one day monitor a patient’s bone health from inside their own bodies.

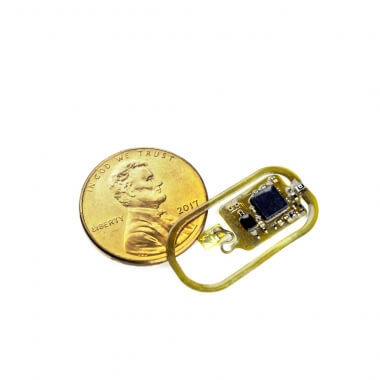

The microchip, which is as thin as a sheet of paper and about the size of a penny, uses wireless technology to keep track of the bone’s health and its ability to heal after injuries or fractures.

“As a surgeon, I am most excited about using measurements collected with osseosurface electronics to someday provide my patients with individualized orthopedic care – with the goal of accelerating rehabilitation and maximizing function after traumatic injuries,” says study co-senior author Dr. David Margolis, assistant professor of orthopedic surgery in the UArizona College of Medicine, in a university release.

Bone health is a major concern for aging populations

Study authors note that bone fractures due to fragility and conditions such as osteoporosis result in patients spending more days in hospitals than heart attacks, breast cancer, and prostate cancer.

While their new health monitor is not yet ready for trials in humans, the team believes these chips could one day improve the standard of care for brittle bones and other complications from aging.

“Being able to monitor the health of the musculoskeletal system is super important,” says co-senior author Philipp Gutruf, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and Craig M. Berge faculty fellow in the College of Engineering. “With this interface, you basically have a computer on the bone. This technology platform allows us to create investigative tools for scientists to discover how the musculoskeletal system works and to use the information gathered to benefit recovery and therapy.”

Batteries not included

When it comes to attaching a tiny chip to your bones, scientists had to create a computer thin enough that it won’t irritate the muscles which surround the bones. Gutruf adds that muscle movement could also pull a larger microchip right off the bone.

“The device’s thin structure, roughly as thick as a sheet of paper, means it can conform to the curvature of the bone, forming a tight interface,” reports co-first author Alex Burton, a doctoral student in biomedical engineering. “They also do not need a battery. This is possible using a power casting and communication method called near-field communication, or NFC, which is also used in smartphones for contactless pay.”

Another obstacle the UArizona team had to overcome was the natural ability of bones to shed old cells. Just like your skin, the bones also renew their outer layers, meaning a traditional “glue” wouldn’t work for attaching the microchip.

Researcher John Szivek – a professor of orthopedic surgery and biomedical engineering – developed an adhesive containing calcium particles which are similar to regular bone cells.

“The bone basically thinks the device is part of it, and grows to the sensor itself,” Gutruf adds. “This allows it to form a permanent bond to the bone and take measurements over long periods of time.”

How will doctors use osseosurface electronics in the future?

The team believes physicians will be able to attach these microchips to broken or fractured bones during surgery, which will monitor the healing process moving forward. Study authors say this would be key for osteoporosis patients, who often suffer refractures after a major injury.

Knowing in real time how well a bone is healing can help doctors in the future figure out the right treatment options after surgery. It can also inform doctors about when it’s time to remove plates and screws which often hold bones together after a break.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.