NEW ORLEANS — Hurricanes and tropical storms, known as tropical cyclones, are moving slower around the planet, according to a new study from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist James Kossin.

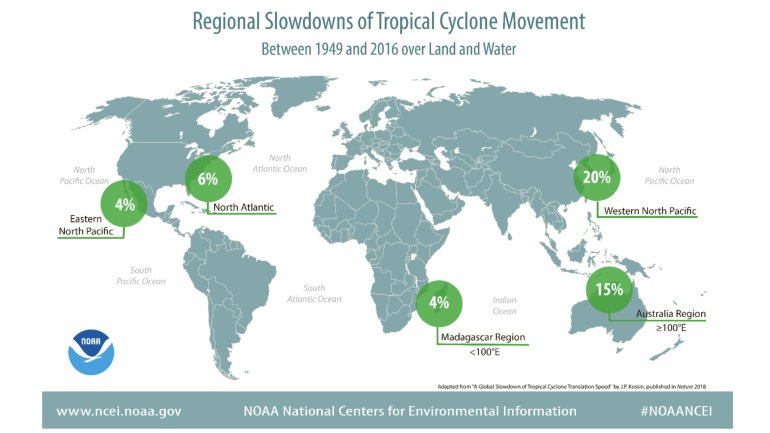

The study, released Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature, showed a 10% decrease in forward speed globally between 1949 and 2016, though there is some variation among ocean basins.

Kossin, who is also with the National Centers for Environmental Information, found a 20% to 30% slowdown over land areas affected by North Atlantic and North Pacific tropical cyclones, respectively.

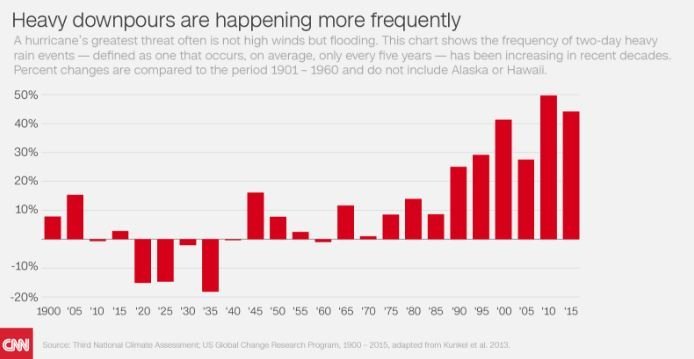

Slower-moving storms mean greater rainfall totals, as seen with Hurricane Harvey in Texas last year.

“These trends are almost certainly increasing local rainfall totals and freshwater flooding,” Kossin said, “which is associated with very high mortality risk.”

According to NOAA, inland flooding accounts for more than 50% of hurricane-related deaths each year.

Although more rainfall is the most direct consequence of slower-moving storms, other impacts can be enhanced as well.

“Long-duration or slower-moving storms, even when weaker, can have exacerbated impacts through prolonged wind exposure [in addition to] flooding,” according to Colin Zarzycki, a project scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research who was not involved with the study.

According to the study, which looked at each ocean basin where tropical systems form, a slowdown in the movement of the storms has been observed in every basin except the Northern Indian Ocean.

Tropical cyclones have slowed more in the Northern Hemisphere, which is significant because that is where a majority of storms occur each year.

The western North Pacific basin, where the strongest systems are referred to as typhoons and super typhoons, sees the most storms annually and has seen the most slowing, at 20%.

Is Hurricane Harvey a preview?

The impacts of slower-moving storms are devastating.

Hurricane Harvey, which progressed at a walking pace over eastern Texas after making landfall in late August, dumped rain in amounts that were a record from a tropical system in the United States: more than 60 inches.

The storm affected 4.7 million people in and around Houston directly or indirectly during the flood and resulted in 68 fatalities, the largest number from a landfalling hurricane in Texas since 1919, according to a report released Wednesday by the Harris County Flood Control District.

In addition to slower atmospheric circulations possibly causing the storms to move slower, the amount of rainfall that the storms are able to dump is increasing as global temperatures climb.

Warmer air is able to hold more water vapor through a process called the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship, which shows that the water-holding capability of air increases about 7% with each degree Celsius of warming.

According to Kossin’s study, combining the additional water vapor available in the atmosphere from 1 degree Celsius of warming —essentially where we are now — with a 10% slowdown from tropical cyclones that he observed would double the local rainfall and flooding impacts.

If Harvey is any indication of what hurricanes will look like in the future, this will create a considerable strain on countries’ ability to respond financially to storms.

Harvey was the second costliest storm on record, behind Hurricane Katrina, totaling $125 billion in damage — of which about two-thirds were uninsured flood losses.

Why are storms slowing down?

Although this study did not investigate directly what is causing the tropical cyclones to slow, it presents a hypothesis that was the basis for the research.

There is considerable evidence that global summertime circulation patterns in the atmosphere are slowing as a result of global warming.

“Storms should be responding to changes in the whole global wind pattern, since they are mostly just carried along in the flow,” Kossin said.

Therefore, it would make sense that if the flow around the hurricanes and typhoons is moving slowly, the storms will also be moving slower, which Kossin believes is what he is observing in the data.

But there are probably more variables at play than a warmer climate putting the brakes on tropical cyclones.

“It is far from clear that global climate change has anything to do with the changes being identified,” said Kevin Trenberth, a senior climate scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Several major natural climate variations occur over long periods, such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, which is similar to the El Niño/La Niña oscillation that can significantly alter global weather but operates on much longer time scales (hence “decadal,” whereas El Niño/La Niña alternate from year to year).

Trenberth points out that this study did not account for these natural cycles, which he said could be behind much of the observed trend.

Kossin admits that there are probably both natural and manmade factors influencing the slowing of storms and recommends further studies using climate models to determine how much greenhouse gas emissions are responsible for affecting the storms’ speeds.

“What we’re seeing almost certainly reflects both natural and human-caused changes,” Kossin said. “We’ll need more formal attribution studies to disentangle these factors.”